Corporate governance—the system by which a company’s board of directors and management executives align themselves with shareholders’ interests in order to make strategic decisions—can be a catalyst (or constraint) to value creation. Value creation is a product of business fundamentals (what the company actually does and how it performs) and investor perceptions (how the market prices the company’s expected future performance). Effective corporate governance enhances these two elements, primarily through greater transparency and more effective decision making, and thus generates more value for shareholders.

Today, well-functioning boards of directors play an increasingly important part in shaping corporate performance and investor perception. In addition to their checks-and-balances roles, boards’ strategic guidance, oversight, and effective decision making can provide invaluable direction and support to companies as they grapple with the challenges of globalization, enhanced business volatility, and intensifying levels of competition.

Yet these are not the roles that typically come to mind when one thinks about best practices for board governance. Instead, people tend to focus on standard guidelines for everything from directors’ roles and responsibilities to information disclosure. However, we’ve observed that following these best practices, as traditionally defined, does not ensure success. Among companies that do achieve best-practice corporate governance, outcomes in performance and quality vary widely. In other words, there is more to governance best practices than most people think. Consider the following example from a client of The Boston Consulting Group, a major Brazilian company and one of BCG’s Global Challengers. (The Global Challengers are BCG’s list of 100 fast-growing companies from rapidly developing economies. See the report The 2011 BCG Global Challengers: Companies on the Move.)

The company’s CEO shared with us his concerns about the difficulty he was having getting all of his board members involved in board discussions. At the same time, some board members confided to us that they felt in many ways shut out; for instance, they felt that the information that management was giving them was inadequate. As a result, decision making was often suboptimal and slow. Ultimately, these difficulties prevented the board from addressing the company’s most pressing concern: the dramatic global slowdown that threatened demand and required urgent action.

We reviewed the board’s corporate-governance practices. The board was doing everything right—in theory, at least. It was adhering to required practices and had adopted the major recommendations prescribed by leading governance institutions. So what was the problem?

The Limits of Existing Best Practices

Our client’s experience inspired us to analyze the corporate-governance best-practices guidelines of a diverse group of institutions, including the New York Stock Exchange, the NASDAQ, and BM&FBovespa. As we suspected, the overwhelming majority of best practices focus on stipulating the attributes of the various governance bodies. Approximately 45 percent of the best practices defined for boards relate to disclosing information and holding meetings, and more than half of the best practices delineated for executive management relate to information disclosure. In essence, most emphasize composition and transparency, with little guidance on the decision-making process. Interestingly, these standards did nothing to prevent some of the most egregious corporate-governance scandals, such as those of Enron and WorldCom—two companies that had been considered models of corporate governance prior to their downfalls.

We then decided to probe for more answers by conducting in-depth interviews with board members, executives, and board secretaries at top-performing companies in sectors as diverse as consumer goods and oil and gas, as well as with global experts on the topic of corporate governance.

In the end, we discovered that what our CEO and his board were experiencing was fundamentally a matter of poor dynamics and lack of engagement—issues that are missing from most corporate-governance guidelines.

Moreover, our analysis revealed that formal guidelines and policies, largely designed to clarify roles and promote transparency, are effective only as long as the underlying culture induces people to embrace them. Without the right values and culture, the most impressive board roster or the most ironclad policies and safeguards in the world cannot prevent reckless or inappropriate corporate behavior. Just as important, policies that flatly ignore everyday realities—such as the time constraints that most directors, as successful leaders, face—are doomed to fail. Adding requirements without implementing efficiencies is no way to ensure that best practices can actually be realized.

Out of this analysis, we identified a new set of factors that we believe play an equal, if not more important, role in fostering effective corporate governance.

The Devil Is in the Details: Four Hidden Factors

The real key to effective governance lies in its “hidden” side, practices and processes that are often overlooked precisely because they appear to be mere details. In fact, these details—individually and collectively—have a tremendous impact on governance. Consider the following:

- How well does the board operate as a team, from its interpersonal dynamics to its decision-making capability?

- Do its often-invisible processes and workings create a culture that promotes cooperation and efficiency?

- How can boards foster and sustain engagement, positive team dynamics, and an unwavering focus on the issues that matter most?

Addressing the “hidden” factors can create an environment that facilitates proper flow of information, preparation of members, and setting of priorities. In such an environment, boards can fulfill their overarching purpose: better decision making and improved investor perception, which are the catalysts to superior value creation.

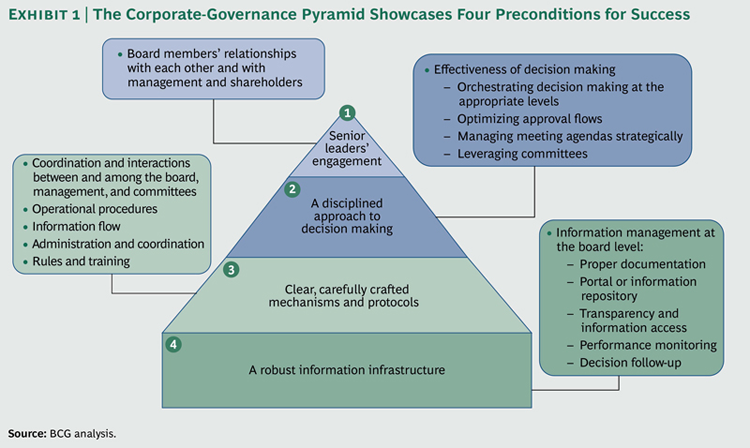

Consider our pyramid of four hidden factors—the preconditions for achieving corporate-governance success:

- Senior leaders’ engagement

- A disciplined approach to decision making

- Clear, carefully crafted mechanisms and protocols

- A robust information infrastructure

The pyramid structure reflects the hierarchy of interdependencies. (See Exhibit 1.) Engagement, the hardest factor to achieve, depends on the three lower layers of factors being firmly in place. The information infrastructure is at the base of the pyramid because it supports all the other factors.

These four factors won’t apply to all companies in the same way; there is no one-size-fits-all approach. In implementing them, each company must consider its own particular characteristics and circumstances: its industry, ownership structure, organization, operations, and culture. It’s equally important to weigh the balance of power between the board and the CEO and how evolved the company’s governance policies and practices are.

Factor 1: Senior Leaders’ Engagement

Clearly, the different operating models of boards call for different degrees of board engagement. In addition, engagement levels aren’t always static: special circumstances call for heightened levels. What we’re talking about is achieving optimal engagement on the basis of what’s appropriate for any given model.

Sometimes, inadequate engagement is simply a function of having individual directors who are passive or lack commitment. More often, though, it stems from any number of factors, such as the following:

- The lack (or unbalanced mix) of capabilities among directors

- An ambiguous or undisciplined decision-making approach

- Differing views of the board’s role

- Members’ limited access to crucial information

- A poorly established relationship between directors and controlling share-holders or management

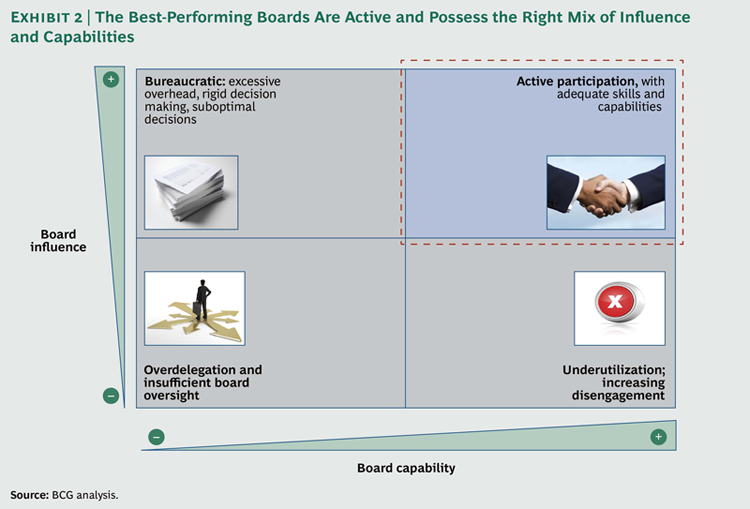

Whatever the cause, weak engagement can damage board morale and fuel divisiveness. At the extreme, it can result in a board that is either bureaucratic and inflexible or unable to fully utilize board members’ capabilities. It can lead to management without checks and balances and with ineffective, if not unhealthy, board-management interactions. The best-performing boards are those that are active and that possess the right mix of influence and capabilities. (See Exhibit 2.)

Companies can use many strategies to strengthen board members’ engagement. It’s worth remembering that engagement starts at the top. Board chairs can play an active role in engaging members simply by being model board members. One chairman we know devotes 50 percent of his time to his governance role. He personally revises the board meeting’s agenda, prioritizes the order of topics for discussion, and even allocates specific time slots for each topic. He closes every board meeting with an around-the-table check, asking directors how they might improve the dynamics for the next meeting.

In boards with appointed members, chairs can also use their influence to recommend board members who will embrace their role energetically.

Create a board competencies matrix. A board’s roster may look good on paper, but that doesn’t mean that the right competencies are represented or are in the right mix. Boards should delineate the key competencies that will allow them and their committees to adequately supervise and advise management. The matrix can serve as a guide for appointing directors and board committee members. And it can be used for board self-assessments (see the next section) to pinpoint capability gaps.

Conduct a self-assessment. Although defining board members’ competencies is a fairly objective process, it does not reveal how committed members are to their role. It will neither reflect their interests and perspectives nor reveal whether they feel they’ve got the right tools and information in hand to make decisions.

Most boards are so preoccupied with getting through the crowded meeting agenda that they never take the time to consider the mechanics of how they run the processes and procedures by which they execute their work, along with the dynamics of their interactions as a team. In Brazil, for example, fewer than 25 percent of the top 100 companies that we studied regularly assessed their board.

Regular self-assessments can provide important insights on key weaknesses in the governance system and help the board identify improvements that could yield the greatest impact. They also offer an implicit benefit: the mere act of conducting a self-assessment influences behavior, creating pressure to perform.

Ideally, the assessment should include a collective as well as an individual assessment of each board member. Beyond helping to pinpoint any weak links, individual assessments can provide board members with constructive feedback, an opportunity that high-performance individuals do not always have—and yet are often quite receptive to.

Craft a declaration of commitment from the board and management. Doing so establishes a clear understanding of the individual and collective responsibilities of directors, executives, and controlling shareholders. The declaration should include an interaction philosophy, a confidentiality policy, guidelines for appointments and designations as well as for training and development, and a blueprint for decision making. Above all, the declaration should reflect a common philosophy of value creation for the business. This will guide board members and management in making key decisions, such as whether to increase dividends or reinvest in the company.

Factor 2: A Disciplined Approach to Decision Making

No board can be expected to make sound decisions without the right information in hand, without open lines of communication, or without clear governance processes and protocols. Yet for many boards, these elements are often missing. Important but nonstrategic matters that should fall within management’s jurisdiction sometimes land in the board’s lap, while truly strategic issues that merit the board’s deliberation are dealt with by company management. Complex issues that merit preliminary analysis by a committee sometimes end up on the main board agenda prematurely, crowding out other matters that are ready for deliberation.

A host of other inefficiencies can impede the decision-making process, from less-than-ideal approval flows to poor meeting dynamics that distract members from the most essential issues. Underutilized or ineffective committees, ambiguous deadlines that create confusion, the absence of confidentiality protocols or guidelines on appropriate deliberation times—all can hamper decision making. Many of these inefficiencies can not only block the board’s ability to respond swiftly to critical company challenges but also undermine the quality of its decisions.

In an effort to ensure proper oversight, boards can also go too far in the other direction. Too much centralization can create needless delays, in turn impeding the company’s ability to execute or to respond in a timely fashion to external change.

Boards can adopt any of a number of measures to orchestrate, streamline, inform, and improve their decision making.

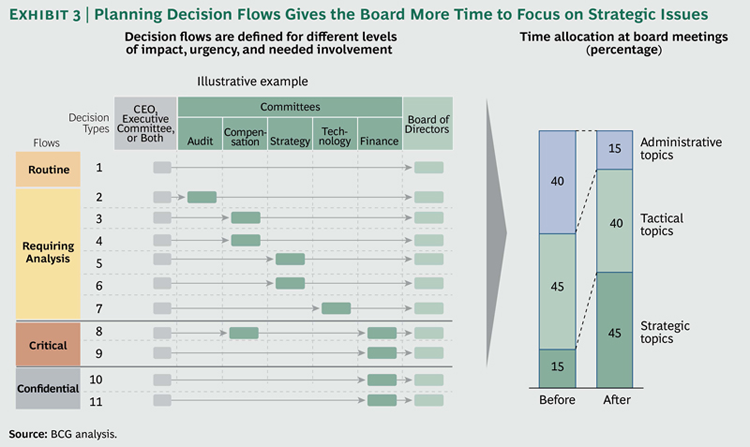

Review managements’ approval levels—and segment decision flows—by topic. The goal here is to ensure that the right parties are dealing with the right types of decisions in the right order. Which decisions should be delegated to management? Which ones might require preliminary review by a committee? Which ones should go straight to the board? Which ones might require advanced consultation and alignment with controlling shareholders? Segmenting approval flows by topic facilitates in-depth analysis (clarifying when certain committees or other types of expertise are warranted). It also helps identify the types of decisions that have urgent deadlines, are confidential, have any statutory restrictions or requirements, or should be supported with additional data. Finally, the process prevents decision bottlenecking. It ensures that managers have the discretion they need to make decisions—and that their decisions are visible to the board. It also ensures that the board is freed up to focus on important elements of its mandate, such as issues of true strategic importance. (See Exhibit 3.)

In evaluating approval levels, directors should first decide whether current levels allow for sufficient autonomy and agility while properly controlling and mitigating risk. Analyzing the company’s recent performance under current levels and assessing relevant benchmarks is useful. Boards should review approval levels on a regular basis, to ensure that they match current business realities and company focus.

Leverage committees to maximize their impact on board effectiveness. Many boards fail to capitalize on the analyses their committees produce. That means they also fail to take advantage of the other benefit that committees provide: alleviating the load of nonurgent issues for the board. To ensure that committee work is integrated into board decisions, the board should review and, if necessary, redefine how its committees are structured. It should look at their activities, their timelines, and the roles of their individual members. In addition, it should establish standard channels and systematic opportunities for allowing committee intelligence to get into the board’s hands when needed. Not all committees need to be permanent, either. A temporary committee can be useful for ad hoc initiatives, such as exploring a potential acquisition or the possible need for an enterprise-wide IT overhaul.

Create a fast track for urgent decisions. Boards should define in advance the types of issues that justify rapid approval and establish procedures that will facilitate speedy decision making. They must consider ways to get the necessary information to decision makers quickly and determine which communication channels (videoconference, phone conference, or e-mail, for example) are the most appropriate. This is particularly important in an era of increasing volatility and uncertainty, when problems can rapidly devolve into crisis.

Modify the organization of board meetings. Agenda management may seem minor, but it can have a tremendous impact on effective decision making. Typically, agendas are developed in a way that presumes equal importance for each item by allocating equal time. That approach almost ensures that critical issues, especially those that aren’t at the top of the schedule, will be shortchanged. In planning the agenda, members should consider the relative strategic relevance of each item and allocate time accordingly. That also means minimizing the time allotted to issues already explored in depth beforehand in selected committees.

Factor 3: Clear, Carefully Crafted Mechanisms and Protocols

Clearly defined governance mechanisms and protocols are essential for supporting the board’s mission and for carrying out the many activities that constitute corporate governance.

The notion that well-thought-through processes support higher-level activities is hardly rocket science. Nonetheless, it is surprisingly absent among many boards. So interactions between board and management are sometimes marred by poor information flow. Some boards spend more time trying to schedule meetings than they do framing the strategic agenda. Others don’t establish adequate transparency in their dealings with “related parties,” in which conflicts of interest may exist. Still others overlook the need to educate new directors about the company, its strategic challenges, and their role as directors.

What can boards do to shore up their governance mechanisms and protocols?

Develop a calendar of yearly meetings, with key themes predefined on each meeting agenda. By planning when important themes will be covered in meetings and committees, boards can highlight and anticipate issues, allowing participants time to prepare. An annual meeting calendar should include recurring annual decisions (such as approving the budget and strategic plan) and key strategic topics (such as the industry landscape, the macroeconomic environment, and competitors’ activities), while leaving room for ad hoc items (such as M&A opportunities).

Set rules for handling transactions that potentially involve conflicts of interest. Many guidelines, both statutory and best practice, address the appropriate means of dealing with related parties that potentially represent conflicts of interest. But it’s important for boards to use the available guidelines to create their own clear-cut rules outlining behavior for related-party transactions. Well-crafted rules should define types of related parties, describe potential conflict-of-interest situations, and establish disclosure policies and controls. Such transparency will help protect the company’s—and shareholders’—interests and help cement investor trust.

But just as important is ensuring healthy dynamics that foster trust among members during such transactions, given that members often represent the interests of the very shareholder groups that may constitute “related parties.” A foundation of trust will reduce the opportunity for conflicts of interest in the first place.

Create an induction program for new directors. Such a program can shorten new directors’ learning curve and help them get quickly integrated into the board’s work. The induction program should introduce them to the company’s operations, strategy, and significant challenges. (See the sidebar “Member of the Board 101.”)

Establish a governance office (with an appointed officer) to orchestrate the organization’s corporate-governance processes. A governance office is more than just the official record keeper for the board and its committees; it is the orchestrator of the four factors presented in this report. It ensures that all the processes, players, and tools are in place, aligned, functioning well, and always being improved. From overseeing information flow among directors and between the board and management to coordinating strategic and legal matters, the governance office is in effect the board’s administration and execution arm. Some boards might prefer a governance officer with a business background; others, one with a legal background. The choice will also depend on who has more influence (the board or management) and on the complexity of the company’s stakeholder relationships.

Factor 4: A Robust Information Infrastructure

A robust information infrastructure helps support the flow of information that board members need in order to exercise their role. It involves facilitating both access to information and flow of information between and among governance parties, documenting decisions and actions, and providing tools for unfettered communication.

Its importance seems self-evident and fundamental, yet many boards make do without one. Inevitably, the other three essential factors are impaired: processes are weak or broken, engagement suffers, and decision making falters.

Directors at many boards frequently have trouble obtaining or accessing important information, such as current performance indicators, documentation of important deals, and the status of decisions already implemented. Without such crucial information, it is difficult for boards to make decisions or follow up on past decisions to evaluate outcomes. Directors risk facing a bottleneck, having to redo work, or worse—if there’s not enough time—being forced to make decisions on the basis of a partial or inaccurate picture.

Fortunately, many elements of a sound information infrastructure are relatively straightforward to implement.

Create a corporate-governance portal. A portal promotes focus, agility, and transparency between board members and management. Typical content comprises board documents, supporting material for meetings, documentation of past decisions (including assumptions used), implementation reports, company performance (past, present, and targeted), industry reports (focusing, for example, on markets, competition, and trends), and relevant information from public sources—basically, the full set of information that supports board resolutions. Overseeing the corporate-governance portal is one of the primary responsibilities of the governance officer in his or her orchestrating capacity. A portal manager should be appointed to coordinate, centralize, and publish content. Interestingly, some companies encourage the use of the portal by providing directors with electronic tablets, for easy, secure portal access. (See the sidebar “Striking the Right Balance with an Information Portal.”)

Develop standard approval templates to get information to members promptly. Whether the board is pondering an acquisition or a major capital-improvement project, templates for information approvals (to assess valuation assumptions and financial data, for instance) help ensure that members get the information they need in a timely manner. Templates also foster objectivity by standardizing the information criteria for key areas of decision making.

Introduce systematic follow-up reporting. Boards should, but don’t always, know the outcome of their decisions. Follow-up reporting provides an objective record to help them monitor the results of their resolutions. A variety of approaches can be used, with varying degrees of detail, from exception reporting to a continuous log that details activities.

Create standard presentation formats. Quality and consistency in presentation formats (whether for quarterly financial reports or updates on HR programs, for example) help board members absorb information more readily, avoid distraction, and adhere to meeting schedules.

Board and Management: Partnering for Value

The age of the almighty CEO may well be over. Leading a company today has become a far more complex and more pressurized endeavor, thanks to globalization, market and economic volatility, more influential stakeholders, and more complicated business alliances and partnerships. The sheer speed of business compounds the challenges of due diligence and timely decision making. Moreover, all of these pressures have taken a toll on the “C suite”: we’re witnessing shorter CEO tenures, higher CEO turnover, and executive posts going unfilled for longer periods.

In short, it’s become increasingly important for CEOs and senior executives to navigate the business landscape with the support, strategic guidance, and collective wisdom of a well-functioning board.

Yet a board cannot function well when its members and company management distrust each other, when crucial information is routinely missing or late, when meeting agendas are overfilled with nonstrategic matters. These disconnects impede cooperation and impair decision making. Ultimately, they can result in an underperforming board that, rather than mitigating company risk, amplifies it.

Corporate governance extends beyond compliance with rules and protocols. It is also about giving the company the power to overcome significant challenges and seize opportunities that build enterprise value. Truly effective governance requires a robust information infrastructure that supports transparency and timely information flow. It requires processes that ensure the efficient and judicious use of time and resources. It calls for an approach to decision making that lets management and the board support, but not impede, each other in classic checks-and-balances fashion. These prerequisites in turn foster cooperation and engagement—the most critical ingredients for effective corporate governance.

Given that the all-powerful CEO is likely a thing of the past, we believe firmly that there is no longer room for laissez-faire boards or board-management power struggles. The framework described in this report is a powerful way to cultivate the partnership between CEOs, their teams, and their boards—and to govern the company wisely and skillfully to sustained value creation.

How well does your company apply the practices of value-focused corporate governance?

--

Republished with permission from BCG Perspectives, a publication of the Boston Consulting Group. For more, visit bcgperspectives.com.